Conflicting appellations

Business desire and identity to defend: why is there so much conflict over Doc? Physiological fact or growing malaise?

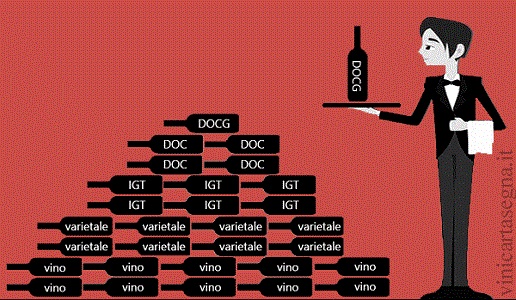

by Fabrizio Carrera, taken from Cronache di Gusto - But is excessive conflict in the name of Docs a symptom of malaise? It seems to us that Italian wine is increasingly divided between a desire for business and an identity to defend. Perhaps it is a physiological phenomenon with which we have always lived and never noticed. But we are seeing increasing signs of war. And yet if we look at the numbers, the Italian wine denominations, between Doc, Docg and Igt, are a two-speed world. In Italy there are 525 denominations, of which 334 DOC, 74 DOCG and the rest IGT, a world record that seals the great Italian biodiversity. But if you look closely, as experts know, there are at most a fair 20% of denominations that really work. Which alone represent more than three quarters of the entire certified production. Perhaps the malaise is already starting from there.

What's certain is that in recent months the trade newspapers (and not only that, there have also been Corriere della Sera pages) have been forced to deal with appeals, parliamentary questions, speeches by the Minister, pending cases in the Council of State, cold wars over types of wine and names of grape varieties. The last case in order of time concerned some Sardinian denominations (see here). In summary: the Region of Sardinia has modified the specifications to allow the use of the name of the vine (Vermentino but also Carignano) in the Igt Terre dei Nuraghi brand labels. And the arm wrestling starts. Producers divided. Some protection consortia that are compacted against the Region. An appeal to the Tar. And after eight months the ruling that gives reason to the association of producers Igt Terre dei Nuraghi that can continue to use on labels some of the names of the most important grape varieties from the commercial point of view for the island.

The Sardinian one is only the most recent case. But in recent months other wars have broken out. That of the Primitivo and the Apulians who were frightened at the idea that the Sicilians, in addition to producing it, could also include it on the label; or that of the Chianti Consortium, which in November, in an assembly, decided on the possibility of producing wines of the Gran Selezione type, just like the cousins of Chianti Classico who started it six years ago with surprising commercial results. At the moment the consortium chaired by Giovanni Busi has not gone ahead with the decision. But the top management of the Gallo Nero were ready to react to what many called a real act of war. At stake is a typology that represents 6% of the 35 million bottles produced in Chianti Classico but in terms of value today is one of the flagships of the entire territory.

Then there is the Doc Sicilia case, the most thorny for various reasons: not only because from a judicial point of view it has already reached the Council of State, but also because it touches on the nerve centre of the scaffolding with which some Italian DOC wines were born; because it divides a historic and prestigious brand such as Duca di Salaparuta (for almost twenty years owned by Illva di Saronno) and a consortium of the most dynamic and full of prospects such as Doc Sicilia, which today puts about one hundred million bottles on the market and is exploiting the oenological and commercial potential of a region that up to a handful of lustres was famous for bulk sales.

Obviously there are many players in the field. The ministry, which is there to play a vigilant role, is almost always involved, taken by the jacket, called to take a stand. When in reality the ball is always in the hands of the producers and the leaders they elect. It is they who determine the choices, the strategies and therefore the level of conflict.

The Doc Sicilia is the most thorny case because however it ends up, it will leave an open wound and a certain discontent in a productive world that has never been completely compacted around a single vision. In all these cases of conflict, but more markedly in Sardinia and Sicily between the Doc consortium and the Duke of Salaparuta, there has been a lack of dialogue. Talking is always good. It is likely that it has not happened. Or it wasn't enough. Those who govern wine, territories and producers must very often wear the shoes of a diplomat and resort to concerted tones. In Sicily it was necessary to avoid the point that a company could make an appeal so pregnant with consequences against an entire consortium. Those with governance had to play on tact and tactics. But diplomacy is like courage. If you don't have it, you can't give it away.

Without thinking that this conflict makes law firms happy. Barack Obama, the former president of the United States, once said that his dream was a country, his own, with fewer lawyers and more engineers. I don't want the togas of Italy, but I think Obama was right. And an administrative lawsuit entrusted to glittering law firms has significant costs for the entire wine community that clings to an idea of territory.

Italiano

Italiano