Interview with Mario Fregoni

Professor Fregoni, professor of Viticulture at the Catholic University of Piacenza and former president of the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV), interviewed by DoctorWine talks about Primitivo di Manduria and the critical issues of the wine sector in Puglia.

"Salento excellence of a territory. Vinum Vita Est" is the title of the debate held in Ugento, a small town in the heart of Salento. The speaker and undisputed protagonist of the event was Mario Fregoni, professor of Viticulture at the Catholic University of Piacenza. He was president of the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV), currently serving as its honorary president, and was chairman of the National Doc Wines Committee and drafter of Law 164/92 on designations of origin. With him we addressed some of the most debated issues of the moment, focus of the chat the Primitivo di Manduria and the current critical issues of the wine sector in Puglia.

DoctorWine: You wrote that Primitivo di Manduria "is a grape variety that represents an Italian and international value." It is probably the most iconic in Puglia. What are the reasons for its success in Italy and abroad?

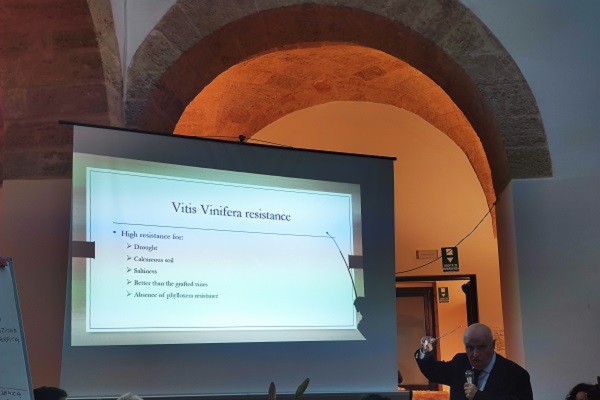

Mario Fregoni: Primitivo di Manduria is a grape variety that adapts well to climatic changes, it is resistant to drought, salinity, and during the summer the leaves are able to decrease transpiration because they close and protect the stomata on the lower page. It is well known that Primitivo di Manduria is a high quality grape variety and has been used for decades in the North to improve the quality of other wines.

DW: Large inventories and lower costs were until recently the main concerns of producers in the area, the arrival of downy mildew has turned everything upside down. Is the current vintage in the balance, in your opinion, or is it just scaremongering? can the aforementioned inventories come in handy, and what interventions do you suggest?

DW: Large inventories and lower costs were until recently the main concerns of producers in the area, the arrival of downy mildew has turned everything upside down. Is the current vintage in the balance, in your opinion, or is it just scaremongering? can the aforementioned inventories come in handy, and what interventions do you suggest?

M.F.: There are many regions, especially in the South, where downy mildew has almost destroyed the entire crop; the attacks are a consequence of the heavy rainfall. I've had people call me to ask if it was necessary to do green pruning to resume vegetation because the blight has destroyed both the bunches and the vegetation. It is certainly not a vintage to remember but the trend is not the same everywhere, in Sardinia there is a magnificent harvest. In some areas stocks can replace this year's missed harvest.

DW: Producers of "dry" Manduria are deciding to apply for recognition as a DOCG, thus joining it with "natural sweet," already a DOCG. However, there seems to be no contemporary demand for recognition of a spillover DOC, leaving this function to the Igt Primitivo del Salento, which affects a much larger quantity of producers than Manduria. A consideration of yours in this regard?

M.F.: A designation is a geographical indication that identifies a food product by linking it to the territory of origin, where there is a Docg there is also an underlying Doc, usually. The production areas with greater sales success abroad are those that have the full pyramid subdivision, that is, Docg, Doc and Igt. In the case of Primitivo di Manduria, a Doc called 'Manduria doc' or 'Rosso Manduria doc' is necessary; I don't understand why the opportunity for a spillover Doc should be passed up. The absence of the Doc of effect is a proof of the lack of knowledge of the Italian wine market in the national and international sphere.

DW: At the conference in Ugento he reiterated that the climate is becoming tropical. Viticulture is moving north, in the Champagne area and in England there are already experimental plantings to cope with this difficult situation. The current climate changes are part of historical ebb and flow, should we be surprised or think about a new management of viticulture with the area under vines in danger of shrinking?

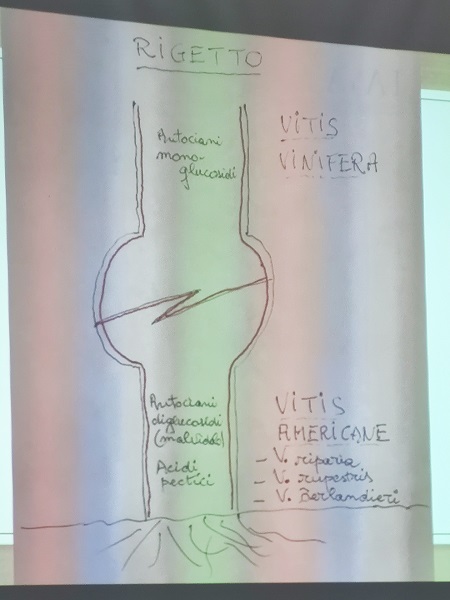

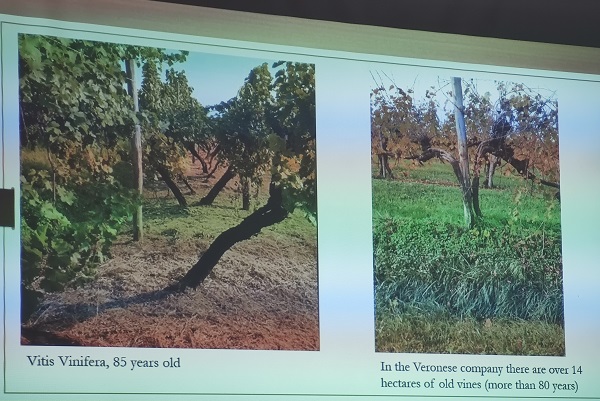

M.F.: Historical courses and recurrences are nothing new, what has already happened in the past punctually returns. But we are well aware that atmospheric warming is due to increasing CO2 emissions Current emission volumes are steadily increasing from 1990 to 2021, they have increased by 66.6%. Atmospheric warming needs to be limited by reducing carbon dioxide emissions; in the wine sector, it is possible to reduce the carbon footprint by selecting water-efficient varieties. For 8 thousand years we have been growing Vitis vinifera franca di piede without irrigation, in Apulia we could think of returning to franca di piede, which is more resistant to drought, especially in sandy areas and adjacent to the sea, there phylloxera problems are absent, the soil does not allow life to the troublesome North American insects.

M.F.: Historical courses and recurrences are nothing new, what has already happened in the past punctually returns. But we are well aware that atmospheric warming is due to increasing CO2 emissions Current emission volumes are steadily increasing from 1990 to 2021, they have increased by 66.6%. Atmospheric warming needs to be limited by reducing carbon dioxide emissions; in the wine sector, it is possible to reduce the carbon footprint by selecting water-efficient varieties. For 8 thousand years we have been growing Vitis vinifera franca di piede without irrigation, in Apulia we could think of returning to franca di piede, which is more resistant to drought, especially in sandy areas and adjacent to the sea, there phylloxera problems are absent, the soil does not allow life to the troublesome North American insects.

DW: The breeding form of the future what will it be?

M.F.: In the world, in America and Australia especially, espalier is the most common type of farming. Espalier uses less water and is mechanizable, although I personally prefer manual harvesting. Mechanical harvesting becomes necessary because of labor shortages, reduces labor time and, by allowing operations to start at the right time, is more timely in relation to the different ripening times of the vines. Of course, manual harvesting allows grapes to be selected according to their stage of ripeness and health status, but there are now grape harvesters that can optically select and discard unsuitable berries. And, in less advanced grape harvesters, well-regulated shaking organs prevent green and desiccated berries from being discarded. Qualitatively, the espalier form could match the sapling, but the latter has an edge: good resistance to tense and brackish winds, excellent adaptability to poor and drought-prone soils, low production per vine and thus high quality grapes. In terms of water consumption to obtain one liter of wine, the sapling uses 350 liters of transpired water, the espalier 450 liters and the marquee 700.

DW: What are the trends of the future and what do you suggest to the Apulia industry to improve?

M.F.: Based on what I have already said, it is necessary to act on three points: choice of variety, selection of free-ranging vines, and a lower, mechanizable training system. In the near future, I am sure, the vine will not have enough water available, consider that we already lose 5 thousand hectares a year of unseeded rice due to water shortage. These are worrying figures, you know that in China and India rice and water are essential to feed the large population. In Spain, for many years, the cultivation of the vineyard area has been conducted without water in the 3 million hectares of vineyards, recently a new water resource management strategy has been adopted to switch from relief irrigation to physiological and sustainable irrigation to optimize the production efficiency of the vineyard. As a result, the vineyard area has been reduced to 1 million hectares by doubling the irrigation and production capacity. Of course, we forget quality, that's another thing. You have to know how to irrigate and know the right periods and quantity, reduced water stress is good for the vine, from veraison to ripening, irrigation is considered a forcing.

M.F.: Based on what I have already said, it is necessary to act on three points: choice of variety, selection of free-ranging vines, and a lower, mechanizable training system. In the near future, I am sure, the vine will not have enough water available, consider that we already lose 5 thousand hectares a year of unseeded rice due to water shortage. These are worrying figures, you know that in China and India rice and water are essential to feed the large population. In Spain, for many years, the cultivation of the vineyard area has been conducted without water in the 3 million hectares of vineyards, recently a new water resource management strategy has been adopted to switch from relief irrigation to physiological and sustainable irrigation to optimize the production efficiency of the vineyard. As a result, the vineyard area has been reduced to 1 million hectares by doubling the irrigation and production capacity. Of course, we forget quality, that's another thing. You have to know how to irrigate and know the right periods and quantity, reduced water stress is good for the vine, from veraison to ripening, irrigation is considered a forcing.

DW: At the conference you mentioned Liber Pater, one of the most expensive wines in the world made from free-footed vines. Is this a fad of the moment or do you foresee a return to free-foot viticulture?

M.F.: In Latin America, Australia, New Zealand and Russia, free-footed vines have always existed. In the future the water will be saltier, in sandy soils or on the seashore the free-footed vine will come back because it tolerates salinity better, American vines do not.

DW: You mentioned that you can get multiple crops over the course of the year, how is that possible?

M.F.: With the tropicalization of the climate, it is possible to do two harvests a year with a technique that I have already applied in Venezuela and Brazil. Harvest times vary depending on the variety and the time when you put the procedure in place to induce the vine to rest and then start a new cycle. It has been applied for green lemon, clearly the quality goes into oblivion.

Italiano

Italiano